ABOUT

W H Talbot and The Origins of Photogravure

ウィリアム・ヘンリー・タルボットと写真技術の誕生

‘First Photographs : William Henry Talbot and the Birth of Photography’

Excerpts from a review of an exhibition held at the Museum of Photographic Arts, Balboa Park, San Diego, April – June 2003

By Christopher Knight, L A Times, April 5, 2003

Talbot is the man who set certain basic terms by which photography operated for almost the last 150 years. He invented the photographic negative, the process by which light creates a negative image on a piece of chemically treated paper, which can then be reproduced — once or in great quantity — in a positive form.

"First Photographs: William Henry Fox Talbot and the Birth of Photography" was organized by MOPA director Arthur Ollman and curator Carol McCusker in conjunction with Michael Gray, curator of the Fox Talbot Museum at the photographer’s ancestral home, Lacock Abbey in Chippenham, England. Amazingly, it is the only American show ever organized to chronicle Talbot’s pioneering achievement.

The neck-and-neck competition between Englishmen and Frenchmen in the 1830s to establish a photographic process is well known and much studied. But, especially compared with Daguerre, one can only speculate on why Talbot has been so egregiously under-recognized by museum exhibitions.

[The most] illuminating explanations for art history’s tendency to favor Daguerre over Talbot in the story of photography turn on significant cultural differences. Daguerre was a painter and scenic artist for the theater when he developed his hugely popular photographic process. Talbot, by contrast, was a scientist, mathematician, linguist and classical scholar. Indeed, not only wasn’t he an artist, his very frustration with his own inability to draw first got him thinking about a mechanical method for fixing images. France, not England, was the artistic epicenter of 19th century Europe.

And Daguerre was bourgeois, engaged in the lively commercial life of the day, while Talbot was Oxford-educated, patrician and aloof in a stratified society. Post-revolutionary Paris was politically volatile, and well on its way to becoming an intellectually rough-and-tumble center of avant-garde activity. Victorian London preoccupied itself with conscientious managerial pursuits at home and imperialist expansion abroad.

Some of that conscientiousness — and even the imperialism — can be seen in Talbot’s photographs. Many are like inventories. There are photographs of shelves lined with light-reflective silverware and tables set out with accouterments for tea. Family members and visitors to Lacock Abbey are recorded, not to mention various nooks and crannies of the estate, inside and out. He photographed at his alma mater, and during trips to France. He took pictures of plaster versions of favorite sculptures, pieces of lace and leaves of plants. He photographed book pages, and he published the first photo book [called The Pencil of Nature] . [Right: The Bridge of Sighs in Venice]

photographs of shelves lined with light-reflective silverware and tables set out with accouterments for tea. Family members and visitors to Lacock Abbey are recorded, not to mention various nooks and crannies of the estate, inside and out. He photographed at his alma mater, and during trips to France. He took pictures of plaster versions of favorite sculptures, pieces of lace and leaves of plants. He photographed book pages, and he published the first photo book [called The Pencil of Nature] . [Right: The Bridge of Sighs in Venice]

Rarely artful, these forthright recordings of worldly things both large and small show the world coming slowly but relentlessly under the dominion of the camera, rather as Delhi, Bombay and Calcutta came under the sovereignty of Queen Victoria, empress of India. When he made his panorama of cameramen at work, the modern global ubiquity of photographs was presaged.

slowly but relentlessly under the dominion of the camera, rather as Delhi, Bombay and Calcutta came under the sovereignty of Queen Victoria, empress of India. When he made his panorama of cameramen at work, the modern global ubiquity of photographs was presaged.

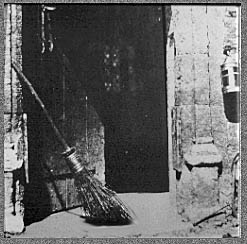

If Talbot’s dreamy, atmospheric photos aren’t aesthetically challenging or even especially pleasing, the way a crisp, glamorous, silvery daguerreotype so often is, there’s no discounting the revolution Talbot’s brilliant innovation launched. Until the recent rise of digital imagery, which doesn’t even need the light of the world to fabricate a picture, making positive prints from negatives was the photographic standard. [Left: The Open Door]

Talbot’s first negative, the guileless one of crystalline windowpanes in his sitting room, is tiny, barely an inch or so big. That he took a picture of light streaming through transparent glass is poetic enough, reverberating as it does against photography’s very method of capturing illumination through a lens. But squint at the little digital facsimile in the show, and its parallel rows of fuzzy black rectangles seem strangely familiar. They resemble nothing so much as a forensic chart analyzing markers of modern culture’s DNA.