At 4:40 am on the morning of March 10, 2010, a security guard at Hachimangu heard a sound like snow falling off a roof. Only there was no snow. Then he heard a thunderous crack, and a dull crash. Rushing out to investigate, he saw the 30-meter ginkgo tree that had stood for 1,000 years was lying on its side. Living since before the existence of Kamakura and Hachimangu, the ancient tree was completely uprooted by winds that reached 12 meters/second during one night.

At 4:40 am on the morning of March 10, 2010, a security guard at Hachimangu heard a sound like snow falling off a roof. Only there was no snow. Then he heard a thunderous crack, and a dull crash. Rushing out to investigate, he saw the 30-meter ginkgo tree that had stood for 1,000 years was lying on its side. Living since before the existence of Kamakura and Hachimangu, the ancient tree was completely uprooted by winds that reached 12 meters/second during one night.

No one was injured.

The demise of the giant tree has been attributed to internal rot, softening of the ground by heavy rains, and strong winds during the first months of 2010, related to ‘El Nino’ weather patterns. The tree was officially designated a natural monument, and has long been known as a symbol of Hachimangu and Kamakura. The chief priest of Hachimangu is too shocked to comment on the matter. The Asahi Newspaper’s headline ‘Gone With the Wind’ evokes the grandeur of this irrevocable loss.

As with the reign of Emperors, time seems divided between before and after the demise of this evocative symbol. Residents and tourists alike have gathered at the site to see with their own eyes whether it is really so. The shock of the loss is palpable, but why such shock? The loss brings back many childhood memories, of school excursions, of dressing-up in kimono or hakata and going to Hachimangu Shrine for shichi-go-san, the festival for girls who are three and seven years old, and for five-year-old- boys. Like a human death, the loss of this once-vibrant being causes people to reassess their own lives, to check that they themselves are still living, and to ask what that living consists of. Whether it’s their work, their relationships with family and friends, their cultural pursuits, or the recognition of their own existence as part of nature, from this shock may come a re-dedication to the human lives and natural environment around us, that we care for them while we and they are still alive.

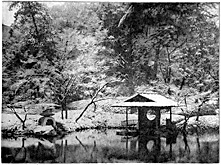

Here is the ginkgo tree at Hachimangu in better days.

The Asahi newspaper of May 12, 2010 carried an article featuring this print and The Kamakura Print Collection workshop.

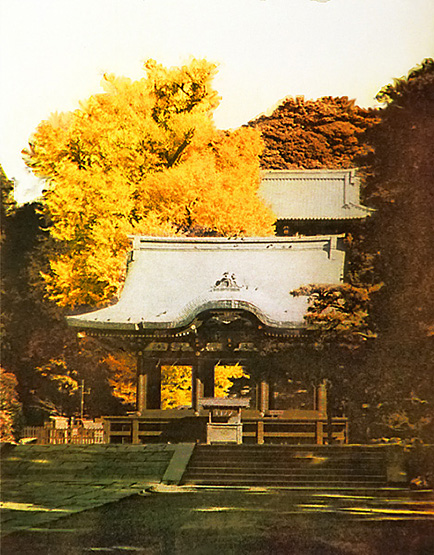

While nothing can replace the Hachimangu ginkgo tree, this one at Myohoin Godaido is equally brilliant (usually in the first week of December), and its setting behind the thatched-roof temple is lovely. Sandstone cliffs (not shown here) shelter the tree from wind and provide a background of depth and majesty.

The ginkgo is the world’s most ancient living tree: It originated two hundred million years ago, in the time of the dinosaurs. Imagine the adaptive ability of a tree whose seeds were once distributed by dinosaurs, which are now distributed by birds. The ginkgo is the only link between pines and ferns, its seed-coverings like those of pine cones, yet clustered like those of palm-ferns. A unique species, botanists have assigned the ginkgo its own genus. (This is a great honor among botanicals.) Some in China have lived for 2,500 years or more. Clues to their longevity lie in their resistance to insect pests, fungal, viral, and bacterial infections, to cold, snow, and ice, CO2, and even to radiation.

Ginkgo trees come in two flavors — male and female. The seeds when they drop and decay give off butyric acid which is also found in rancid butter. If harvested, the seeds can be roasted and eaten, they taste like a combination of pine nut and pistachio.

The leaves, when dried and processed, have been shown in well-designed scientific studies (reported in JAMA and elsewhere) to improve blood circulation and memory, and to prevent acute mountain sickness in rapid-ascent climbing. They may also be useful for treatment of dementia. Ginkgo extract is a $280 million business in Germany, where it is prescribed by doctors (five million times per year) and covered by national health insurance. Further information about the ginkgo tree, including how to grow it, history, medicinal uses, photos, videos, and much else, is here.