June 2020 update: A global pandemic tips the balance toward working at home, for many companies and employees. In addition to the waste of time and energy from the daily journey to offices, mass-transit commuting has proved to be a major spreader of infectious disease. The 2015 essay continues below…

Work, according to convention, is labor performed in factory, office, shop, or farm in exchange for money. By similar convention, leisure occurs at home or on vacation as a respite from labor. Yet the structure of work is changing, with more people working at home (up from 9.2 million in 1997 to 13.4 million in the United States, according to the U.S. Census), more mobile 24/7 workers, more part-time work, and less secure or well-paid formal employment. Automation is reducing jobs, or more accurately redistributing them. Meanwhile more people seek an opportunity to practice workmanship and a sense of belonging among those who appreciate it. For those who achieve this ambition, the spontaneous element of play animates the duty of work.

Work as a Refuge From the Self. If leisure is where we amuse ourselves, work is where we serve others. Modern society generates intense self-involvement – just scan any university catalogue or free-lance outfit, and find uncountable numbers of references to self-improvement, self-development, self-advancement, self-healing, and watch people taking selfies with more self-absorption than the most narcissistic of even a few years ago would have dared. And yet, following a dialectic worthy of Newton or Hegel or Marx, all this self-absorption generates an equal and opposite reaction, driven by a compulsion to serve some entity higher than oneself, to find a refuge from excessive self-involvement, a chance to participate in some higher purpose. Increasingly this takes place outside formal employment.

Derek Thompson cites economist Lawrence Katz’s observation that factories whose sole reason for existence is their ability to produce custom-made goods cheaply are obsolete. With the spread of 3D printing and design software, new-style artisans are custom-designing and manufacturing everything from coffee mugs to printed circuit boards almost as cheaply. Katz thinks the 19th century artisanal economy of blacksmiths, silversmiths, and woodworkers is re-emerging in updated form, using information technology and industrial machinery to make things that would be un-economic for mass-production factories. ‘Makerspaces’, which have evolved from art spaces like the Torpedo Factory in Alexandria Virginia, bring together a variety of these artisanal skills under one roof. The Columbus Idea Foundry, for example, includes shops offering product design, prototyping, engineering, and fabrication, CAD automotive design, hydroponics automation, mobile apps for sales field staff, out-of-the-box ready 3D printers, programs to help students think, create, and develop their ideas, among many others. Unlike a 19th-century style factory that brought people together for central coordination of their labor, these places serve as a place for independent artisans to gather, exchange work, and make outside contacts. They combine the functions of union hall, social club, and innovation-incubator. Markets for spot employment are also growing, thanks to Internet-matching of skills with needs by firms such as TaskRabbit, Craigslist, eBay, Uber, and others.

The 24/7 wired workday re-integrates personal and professional life, enabling time by oneself to generate novel ideas, then turning them to good account if they contribute to communal well-being. A typical Internet session mixes messages from friends, family, business associates, seekers of sympathy, and purveyors of goods, services, and ideas, with social media news, gossip, useful and useless information, images, videos, events of personal significance, and random observations. Through such media, the nexus of mutual help expands and diversifies beyond traditional employers and families, toward people of similar interests and likes regardless of where they live, what their formal jobs may be, or what demographics allegedly define them.

Remember that this now-pervasive virtual world was brought forth in the name of efficiency and productivity. Far be it from the American paragons of efficiency to live in this new virtual world merely for fun. No, it has to enable us to work better, faster, smarter, more connected, and with, as always, more and more information at our fingertips. But something unexpected happened on the way to this greater productivity. It turned out to be immense fun. Worries about the unskilled being left out of the computer revolution proved to be vastly overdone, as billions of people around the world eagerly acquired the skills to navigate cyberspace, find information they need, and even receive academic instruction remotely. And in a world that mints job titles like web designer, applications integrator, user interface engineer, not to mention ‘chief visionary officer’, the overall amount of work to be done is if anything increasing.

Conspicuous Consumption Yielding to Conspicuous Work. Not so long ago, the idle rich sought to distinguish themselves by their consumption – sailing at Hyannis, golfing at Pebble Beach, gambling at Monte Carlo, partying in the Hamptons or on the Riviera, riding to hounds in Virginia. Nowadays, those who indulge in such pursuits are conspicuous by their absence from the top levels of social esteem. Work of a particular kind has become the new mark by which the successors of the idle rich seek to distinguish themselves.

Pebble Beach

This work has nothing to do with earning a living. While it shares many of the superficial characteristics of gainful employment, such as crowded schedules, deadlines, and meetings, the cash flows in the opposite direction. Unlike traditional philanthropy, where the relationship often ends with writing a check, the donors take an active part in the conduct of the non-profit enterprise. An opera company driven into bankruptcy by a profligate manager is revived by a wealthy financier. A school is built in a remote Himalayan kingdom, the donors assisting with construction and maintenance on-site every summer. Education, the arts, the environment, the unfortunate, animal rescue, political candidates of every hue, and myriad other projects and programs are supported, sandwiched in between appointments at culinary establishments of impeccably healthy organicity, and travel to exotic destinations.

These kinds of work constitute a new style of luxury, as distinct from the old-style frivolous pursuits. History is replete with examples of luxury consumption and practices being emulated by the less fortunate and thereby diffusing through the populace. Non-profit rewards are springing up everywhere, from the ‘cultural commons’ of free information-sharing to the barter-economy of consensual communities. The trend is driven by disenchantment with the money economy, with its fiat currencies, corrupt bankers, runaway government debt, and moral bankruptcy. For the vast majority whose livelihood is tied to a job – ‘wage-slaves’, in Marx’s eloquent phrase – informal employment is an increasingly attractive alternative.

The philosopher and mathematician Bertrand Russell proposed in a prescient essay in 1932 that modern society would best benefit from automation through an equitable reduction of work. The worship of work as an end in itself, he wrote in In Praise of Idleness, is a relic of the slave society where a few enjoyed leisure while the many worked overtime. What we really seek is not labor per se, but the enjoyment of goods and services purchased through labor, and above all the free use of our own time. As Russell wrote,

The fact is that moving matter about, while a certain amount of it is necessary to our existence, is emphatically not one of the ends of human life…. We have been misled in this matter by two causes. One is the necessity of keeping the poor contented, which has led the rich, for thousands of years, to preach the dignity of labor, while taking care themselves to remain undignified in this respect. The other is the new pleasure in mechanism, which makes us delight in the astonishingly clever changes that we can produce on the earth’s surface. Neither of these motives makes any great appeal to the actual worker. If you ask him what he thinks the best part of his life, he is not likely to say: ‘I enjoy manual work because it makes me feel that I am fulfilling man’s noblest task, and because I like to think how much man can transform his planet. It is true that my body demands periods of rest, which I have to fill in as best I may, but I am never so happy as when the morning comes and I can return to the toil from which my contentment springs.’ I have never heard working men say this sort of thing. They consider work, as it should be considered, a necessary means to a livelihood, and it is from their leisure that they derive whatever happiness they may enjoy….Good nature is, of all moral qualities, the one that the world needs most, and good nature is the result of ease and security, not of a life of arduous struggle. Modern methods of production have given us the possibility of ease and security for all; we have chosen, instead, to have overwork for some and starvation for others. Hitherto we have continued to be as energetic as we were before there were machines; in this we have been foolish, but there is no reason to go on being foolish forever.

Automation. Automation redistributes work, making some industries and jobs obsolete, raising others up to the heights of demand. In on-line commerce, for example, Web-retail sales in the United States amounted to $320 billion in 2014, growing at 20 percent per year since 2000. Asia-Pacific on-line commerce amounted to $332 billion in 2012, with China’s 220 million on-line buyers spending $110 billion.5 It’s driven by Amazon, Apple, Alibaba, and numerous traditional brick-and-mortar stores that have gravitated to clicks’n’mortar. There’s something about the letter ‘A’ here: apparel and airline tickets are among the biggest items. Maybe anonymity is part of the appeal. But music, games, banking, and movies are also big. And this is only retail, or B2C. B2B is even larger. Just-in-time parts re-stocking is now not only possible, but mandatory, and this is now done in the field, with mobile apps. Compared with snail-mail, the cost savings from this automation of order-taking is enormous. Yet while on-line commerce is removing legions of record-keeping jobs, it is creating other jobs in exception management, customer care, security and privacy, and website design catering to an increasingly mobile clientele, to name only a few examples.

Chaplin, Modern Times

Visualization tools, to take another example, have enhanced astronomical, biochemical, medical, geological, and numerous other practical disciplines of discovery (and video games and story-telling as well). This field alone employs thousands of computer programmers, user-interface specialists, chip designers, applications customizers, and numerous other previously unheard-of categories of workers.

Automobile factory robots

Boring, repetitive tasks are automated not because they are boring and repetitive, but because (a) everything essential is known about them, (b) the savings in time and cost are overwhelming and undeniable, and (c) competitors are doing so, driving costs down and thereby gaining competitive advantage. For car assembly, a human spot welder costs about $25 an hour, a robotic one costs eight dollars. And the robot is faster and more accurate. Robots now perform 10 percent of all manufacturing tasks, according to the Boston Consulting Group; by 2025, that will increase to 25 percent. Everything from semiconductor wire-bonding to soup-can filling and sealing to shipping that can be automated is already automated or soon will be. Amazon alone relies on 15,000 robots for order fulfillment.

That the outcomes of boring repetitive tasks are totally predictable is what allows their functions to be ‘programmed’. Yet even what would seem to be creative endeavors are not exempt. Pop songs and movie plots are now composed by algorithms derived from what has recently sold well. Medical diagnoses are performed by algorithms similar to those that Amazon uses to tell you, annoyingly, what other books were purchased by those who bought the one you are looking at. Automated medical diagnoses are more accurate than those of the average GP. Automated visual analyses of X-rays and blood-test smears can detect signs of disease faster and more accurately than humans. A British robot named Eve has discovered a new anti-malaria drug. Closer examination of the human versions of these activities reveals, however, that they were already highly routinized. Technicians had reduced song- and movie-writing, medical diagnosis and drug discovery to standardized procedures that were only one step away from becoming programmable.

Even before some programmers submitted a computer-generated article to an academic journal of post-modern studies, it had become obvious that there was something formulaic about these articles. Using buzzwords like hermeneutics, post-modern, deconstruct, empowerment, oppression, and the like, the program they devised spit out an article accepted by numerous reviewers in this field and subsequently, was duly (or dully) published, and praised by many readers. Only later was it revealed that the ‘author’ was a circuit board acting under instructions of a few lines of code. (The original spoof article generated by Alan Sokal, Professor of Physics at New York University, Transgressing the Boundaries: Towards a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity, was published in Social Text #46/47, pp. 217-252, spring/summer 1996.) Since then, academic journals have been farmed out to publishers in countries with nonexistent reviewers, where (purportedly) human authors can obtain publication merely for payment of a modest fee ($150 being the typical going rate). Climate scientists and pharmaceutical researchers have been among the most avid users of these ersatz media, a natural affinity since their algorithm-driven models are also highly automated. The latest wrinkle in this trend is that many stock-market analyses are automated, generated entirely by a few inputs from news sources, Fed mouthings, Labor Dept reports, and the standard economic indicators. This too seems fitting, as a great deal of stock-trading itself is algorithm-driven in response to the same signals as are contained in analysts’ reports. Many tweets on Twitter are now also automated. The creativity or spontaneity that had once generated such efforts having been drained from them, automating them was merely a logical evolution.

Why airplanes crash. An FAA investigation into the causes of airplane crashes, released in 2013, found that more than half resulted from the loss of flying skills brought about by over-reliance on the autopilot (Nicholas Carr, The Glass Cage: Automation and Us). Carr estimates that pilots now spend only about three minutes per flight actually flying the aircraft. The inevitable loss of skill, combined with uncertainty during critical moments as to who’s in charge, has often led to disaster. Exactly how this happens is shown in the TV program ‘Mayday Hour’, which recaps the detailed post-crash investigations. In one instance, mud-dauber wasps had built a nest inside the ‘pitot tubes’ that measure airspeed, blocking

Pitot tube

them. Faulty airspeed data relayed to the autopilot caused the aircraft to slow down, and unable to maintain lift due to insufficient airflow over the wings, it stalled and crashed. The autopilot is a complex system, of which some functions may remain on while others are switched off, either by design or by accident. In one unfortunate case, overriding automated steering and banking left the autopilot still in charge of pitch and yaw. With the aircraft exceeding its 25-degree design-limit bank-angle, the autopilot increased engine speed to bring the nose up, resulting in a deadly tailspin. (This design flaw has since been corrected.) Even when pilots are actively flying the plane, over-reliance on faulty ground proximity detectors, altimeters, or storm position trackers have doomed flights that could have been landed safely had the pilots paid attention to the physical evidence.

The chain of command is another airborne hazard. The captain’s sacrosanct authority can be thought of as a kind of ’emotional autopilot’, short-circuiting human error detection. It has led in some instances to senior pilots using their airplanes as instruments of suicide, for religious reasons, due to financial troubles, or pursued by private demons. The problem for others in the cockpit is knowing, as with the computer-based autopilot, when to disable it. Flight crew training now includes watching for signs of instability, procedures for fostering open communication, and taking prompt action in an emergency.

The Dialectic of Artisanship and Industry. Artisanship and industry are by convention seen as opposed to one another. In fact, they are engaged in a dialectic. Just as the self-involvement ethic generates a desire to serve some superior entity, so automation generates its own artisanal improvements and innovations. The steam engine was invented by mechanics who knew from their own experience the power that steam can deliver when heated and compressed. Switchboard operators were long ago replaced by automatic exchanges, but society always needs people with communications skills. Even in the most massive of heavy industries such as steel, specialty steels with nearly hand-crafted alloy concentrations are among the fastest-growing products.

Where there is uncertainty, change, happenstance, unpredictability; where outcomes are indeterminate, the number of variables beyond comprehension, their properties of doubtful quantifiability, the environment one of constant change, there, artisanal work is essential. That is the real world we live in.

Workmanship, far from having been made obsolete by automation, becomes all the more valuable in an automated world. The inherent value of artisanal work is recognized in such institutions as the French Compagnons du devoir whose members enjoy the exclusive right to maintain cultural monuments. Germany and other European countries have similar institutions that maintain the requisite skills along with the buildings. Japan designates as Living National Treasures (人間国宝) practitioners of certain traditional work such as cormorant fishing, kimono-making, and calligraphy that embody national cultural significance.

William Morris

In Britain the Arts and Crafts Movement pioneered by John Ruskin and William Morris urged the superior integrity of hand-made goods of integrated design and manufacture. The landscapes of Gertrude Jekyll and architecture of Edward Luytens similarly celebrated a kind of designed wilderness. Adherants of this style were memorably lampooned by George Orwell as ‘every fruit-juice drinker, nudist, sandal-wearer, sex-maniac, Quaker, Nature Curer, quack, pacifist, and feminist in England’ (in The Road to Wigan Pier). Yet the influence of the Arts and Crafts Movement continues to this day. In America it inspired the Prairie Style which gave rise to such distinguished architects as Frank Lloyd Wright, Charles and Henry Greene, and Bernard Maybeck. The Prairie Style in turn graced the early skyscrapers of New York and Chicago, massive steel structures symbolizing America’s industrial might.

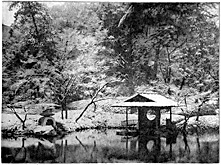

Bois de Moutiers, photogravure etching by Peter Miller, of the Jekyll landscape garden and Luytens house

Artisanship struck a resonant chord in Japan, where Soetsu Yanagi was already championing the mingei (folk-art) style in ceramics, textile-making, and other goods. The potter Shoji Hamada, having studied with the Hong Kong-born British ceramicist Bernard Leach, revived the Japanese wabi-sabi tradition of simple materials and rough design in a community that is still active today. Yanagi’s The Unknown Craftsman (Kodansha International, 1972 and 1989) reinforces the centrality of artisanal work to modern industrial society. Yet mass production also enables many to have otherwise unaffordable goods – a contradiction that discomforted artisanal promoters who preferred democratic to elitist taste. Economist and curmudgeon Thorstein Veblen dismissed wabi-sabi rusticity as ‘an exaltation of the defective’. Yet these very defects, whether they entice the eye of the beholder or not, are essential elements of the learning required to improve productivity.

Western economists typically described Japan’s ’emergence’ as an industrial colossus as a ‘miracle’, betraying their ignorance of the cultural roots of industrial development. Japan’s most successful industries did not ’emerge’ out of the Wharton School, they were grounded in native traditions of workmanship. Toyota, now the largest car company, grew out of a textile-weaving outfit called the Toyoda Automatic Loom Works. Experience with soy fermentation led to a vigorous biotech industry. Japanese workers were already familiar with miniaturization long before that became one of the driving forces of electronics manufacture, which the 14th-generation descendant of a soy sauce manufacturer used to advantage in founding Sony. Japan’s steel industry built on centuries of experience with metallurgy and sword-making. Japan’s real natural resource is its wealth of artisanal tradition that powered its industrial growth.

Amid the wreckage of post-WWII Japan, Donald Keene noted the strength of Japanese culture as a resource for industrial development:

My main occupation in Kyoto was studying Japanese literature, but on one occasion I was asked to be a ‘reporter’ at a conference sponsored by the Institute for Pacific Affairs. My task was to make summaries of the statements made by the distinguished people who attended. About half the participants were Japanese; the rest were Americans, Canadians and British. The Japanese, mainly economists, were convinced that Japan’s future was dismal…. The non-Japanese participants did their best to suggest ways for improving the Japanese economy. An American, after praising the Japanese for their skill with their hands, urged them to concentrate on making delicate objects like fishhooks. The Japanese delegates did not seem to think that their economy could be rescued with fishhooks.

The general impressions of the conference, at least to an outsider like myself, were of resignation on the part of the Japanese and friendly but unhelpful attempts by non-Japanese to cheer them. I could not detect anything positive arising from the discussions.

At no point in the discussions was Japanese culture mentioned. This was perhaps natural in a gathering of economists and politicians, but someone might have pointed out that, despite the hardships that the Japanese people had undergone, the postwar period was a golden age of Japanese culture. The extraordinary outburst of major literature was largely the result of the freedom that had come with the end of Japanese military rule.

Automation and Spontaneity. Automation, as noted earlier, generates a demand for spontaneity. One of the most enjoyable pleasures of walking around is listening to some unknown person practicing the piano. It’s best with an open window, but even in winter, muffled by intervening walls, wind, traffic, how delightful to just stop and listen. The occasional missed note, tempo slowed for a difficult passage, sometimes repeated until it flows better, the careful attention to dynamics – these are more charming than a note-perfect recording. A breath of air, the light glancing off a passing object, something seen only in peripheral vision, might convey the inspiration of the moment. We cherish spontaneity for the same reason we value our freedom — the outcome is unpredictable, unexpected, it cannot be determined by any algorithm, or by the owner of any algorithm. Nor is this just some whimsical preference; it is a vital resource for innovation, without which society cannot advance. With perfect predictability and hence zero spontaneity, innovation disappears (it is not needed).

The ‘perfect predictability’ delusion can occur when experts, those who have cornered the market in a particular intellectual discipline, persuade others that they have all the answers. Typically formulated as the output of computer models too arcane for the average person to understand, their claims to a monopoly of rectitude leave no room for alternatives. Such claims foreclose the possibility of experimentation on which innovation depends.

As Friedrich Hayek put it in The Creative Powers of a Free Civilization:

It is only when such exclusive rights are granted, on the presumption of superior knowledge of particular individuals or groups, that the process ceases to be experimental and the beliefs that happen to be prevalent at the moment tend to become a main obstacle to the advancement of knowledge.

It is worth a moment’s reflection as to what would happen if only what was agreed upon to be the best knowledge of society were to be used in any action. If all attempts that seemed wasteful in the light of the now generally accepted knowledge were prohibited and only such questions asked, or such experiments tried, as seemed significant in the light of ruling opinion. Mankind might then well reach a point where its knowledge allowed it adequately to predict the consequences of all conventional actions and where no disappointment or failure would occur. Man would seem to have subjected his surroundings to his reason because nothing of which he could not predict the results would be done. We might conceive of a civilization thus coming to a standstill, not because the possibilities of further growth had been exhausted, but because man had succeeded in so completely subjecting all his actions and his immediate surroundings to his existing state of knowledge that no occasion would arise for new knowledge to appear.

Hayek’s Creative Powers essay is fundamentally relevant to the expanding scope of social control that information technology enables. Society requires constant experimentation and free competition to advance, not only in the economic realm, but in ethical and aesthetic ideas as well. Interestingly the sort of freedom that is most productive for social advancement is not one’s own, but that of random odd individuals who by some unknown means come up with new and better ways of doing things. Stagnation resulting from the more extreme forms of totalitarian social control is obvious. With less violent means of social control, such as deference to anointed expertise, mass surveillance, or political-correctness, the stagnation is no less real. ‘Mistakes’, in the sense of variance from conventional belief or practice, are valuable resources for experimentation, creativity, and progress. As such, they are to be actively cherished and not merely tolerated. Of course not all mistakes will turn out to be useful, but that is for free competition to sort out. The environment, society, the self change unceasingly, this random variation being the very stuff of experience and innovation.

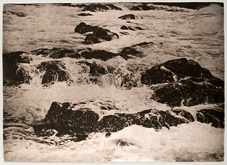

My printmaking experiences have taught me to value mistakes, and in this respect I have a wealth of opportunity. The resist can be under- or over-exposed, the shadows mottled by foul-biting, the highlights unreachable and featureless, the ink too viscous or too thick, too contrasty or lacking clear definition, the paper too wet or too dry to register the ink properly, and so on. A bad day might see a cascading series of errors, each magnified by the previous one. Rarely is there an etching session without surprise. One thing is certain, though: The etching is entirely the result of choices I made. My mistakes are not society’s fault, nor that of anyone else. And this realization is liberating, for it means I can discover the source of my error and correct it. In composition too, my efforts may be successful or not, according to how fully the graphic and extra-graphic aims may be coherently integrated.

As an artisanal practitioner, I suspect that my affection for the imperfect rusticity of the hand-made known as wabi-sabi is shared by many who find the ‘perfect’ precision of mass production to be anonymous, impersonal, cold, and distant. Artistic discovery involves a constant dialectic of observation and imagination, aesthetic experiments that work or don’t work, according to my success or failure in conveying graphically some state of mind, memory, or emotional and philosophical perception. The phenomena of everyday life, such as we all experience, are the raw material of this drama. A spontaneous awareness of the possibilities of design, perspective, line, form, and composition, visualized in the field, is required for an artistic experiment to be successfully realized.