Spring is the time for all creatures to crawl out of their burrows and renew their lives. I travel to the southernmost point of the four main islands of Japan, Ibusuki at the southern tip of Kyushu, to get an early taste of spring. At Ibusuki this begins with my immersion in the hot-spring sands at the edge of the sea.

Preparing for my burial, I lie down on the beach. As an attendant shovels sand onto me, I think of the Kobo Abe / Teshigahara film Woman in the Dunes where a visitor stumbles into a sandpit and is trapped with the beautiful young widow who lives there.

The sand is unexpectedly weighty, and even though I COULD get up anytime, I don’t really want to. As a comforting warmth envelops me, I feel my heartbeat, and every whoosh and push of my arteries, as never before. Far from being a burial, this is a rejuvenation! Steam rises from the beach, as heat from the earth’s molten core percolates just beneath. Here in Ibusuki, I am in touch with the deepest forces of earth and cosmos.

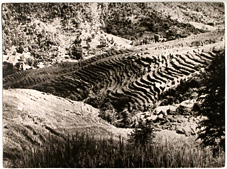

In the volcanic soil created by an ancient explosion of Kaimon-dake, and warmed by the sun above and the earth below, grow soramame — ‘sky-beans’. Sweet to eat right out of the pod, and very fine roasted as well, they grow here year-round.  Dinner at the minshuku, Unagi Kohan (tel 0993-34-1954), steamed over a hot-spring vent, is superb. The family have lived there all their lives. Hot-spring vents supply all their energy requirements, and nearly everything they need is available locally. Geothermal energy supplies a lot of the electricity in the region.

Dinner at the minshuku, Unagi Kohan (tel 0993-34-1954), steamed over a hot-spring vent, is superb. The family have lived there all their lives. Hot-spring vents supply all their energy requirements, and nearly everything they need is available locally. Geothermal energy supplies a lot of the electricity in the region.

Back in Ibusuki, I visit Sakai Shoten (tel 0993-34-0070), a factory that turns katsuo, a smaller version of tuna, into various forms that are a staple of the Japanese diet. In one form, it is solid, preserved after steaming and drying with repeated applications of a special fungus, then sun-dried. The work proceeds with astonishing efficiency and speed, and artistry as well.  Whether fresh or dried, the shape is very important for the supremely exacting tastes of Japanese consumers. Sakai-san explains there is an inherent love of beauty, even (or especially) with food. He demonstrates how the shopper’s hand inevitably gravitates to the more appealingly-shaped fish, and this is reflected in its price — the difference between profit and loss for his company. The dried version, expertly carved, reveals a pine tree, a bamboo leaf, and a plum-flower, the traditional shochikubai, symbols of long life. A pair, masculine and feminine, is traditionally given as a wedding gift.

Whether fresh or dried, the shape is very important for the supremely exacting tastes of Japanese consumers. Sakai-san explains there is an inherent love of beauty, even (or especially) with food. He demonstrates how the shopper’s hand inevitably gravitates to the more appealingly-shaped fish, and this is reflected in its price — the difference between profit and loss for his company. The dried version, expertly carved, reveals a pine tree, a bamboo leaf, and a plum-flower, the traditional shochikubai, symbols of long life. A pair, masculine and feminine, is traditionally given as a wedding gift.

The solid katsuobushi can be shaved into very thin pieces with a box-plane. These are used to flavor rice, misoshiru, vegetables, and other foods. The number of steps, the immense amount of work, and the sheer artistry required to put this on everyone’s table is mind-boggling. In addition to everything else, to meet new food-safety standards, the factory must tag every fish with the date it was caught and the name of the fishing boat.

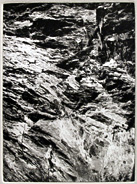

The wealth of historical experience wrapped up in seemingly simple katsuobushi is a real revelation to me. I feel a kinship with my own etching, minimalist, black-and-white images that emerge from the simple materials of ink, paper, and copper. After gazing at a field of nanohana flowers, with Kaimon-dake in the distance, I return to my workshop newly inspired, and happy to have experienced the warmth of Ibusuku and its people.