One day in 1998 with friends in Washington DC, a call came in. ‘Would you like to go on a Silk Road trip’, to Pakistan, Hunza, Gilgit, Xinjiang China, Kyrgyzstan, Almaty Kazakhstan? It took me about two seconds to decide yes. Ten of us — seven Americans, one each Canadian, Filipina, and French — met up in Pakistan for the journey northward. Islamabad with its vast avenues of Saudi-financed buildings was government territory. Neighboring Rawalpindi with its incredibly lively street life was its market-appendage. Amid the rubble-strewn sidewalks and buildings leaning at odd angles, the hustle and bustle of daily life radiated irrepressible energy. To experience this enthusiasm is to understand the overwhelmingly young demographics of Pakistan.

We stopped in Mingaora, a village on our way north. There I noticed an old man sitting on a pile of bricks. He seemed to be passing the time of day, thinking. In fact, he was guarding the bricks. In a country where cow dung is rationed for use either as fertilizer or construction material, bricks are a scarce resource valuable enough to steal if no one is looking. Somewhere in the back-country around there, a goat-herd played the flute. Our guide explained after the serenade that this was a payable event, which we didn’t mind much, the music was lovely.

The gateway to the Swat Valley was marked with vast jacaranda trees filling the sky, flowering with a luxuriant perfume that could have inspired the Shangri-la of Asian mystique. The fertile and prosperous valley teemed with the life of a people peacefully tilling the fields and living in harmony with the world around them.

In the more arid foothills approaching Peshawar, we noticed a long line of trekkers on a far-off rocky trail. They were so far away they looked like a procession of ants. Binoculars revealed them to be people carrying refrigerators, ovens, and electronic goods strapped to their backs. These goods had been smuggled into the port of Karachi and were carried by human mules for sale in the remote back-country. Though electricity was scarce there, one road had power lines that stopped abruptly at a huge compound. Alone in the dry rocky landscape stood this oasis of greenery and electricity. It was, we learned, the home of the ‘King of the Smugglers’, the employer of the trekkers we had seen earlier. The wealth of the country belonged to him and to people like him who controlled whatever commerce was allowed to exist.

Peshawar, near the legendary Khyber Pass, was defended in ancient times as it is now by fierce tribes anxious to keep intruders out of their sovereign territory. No invader, from Alexander the Great to the British and Russian players in the 19th-century ‘Great Game’ to the latter-day Americans, has ever been able to impose its rule on this region. In cities and villages like Peshawar, I walk around early, right after sunup, to watch vendors setting up their street-stands, children going to school, office workers, teachers, women shopping. There were no other tourists besides me. The unmistakable look on everyone’s face wordlessly expressed: ‘Why are you here?’ It was not an unfriendly inquiry, merely one of curiousity, similar to my own curiosity. I found that if I stayed still for ten minutes, I blended into the background and could frame some spontaneous scenes in the camera without being noticed.

For some, the question ‘Why would you want to come to this hellhole?’ appeared in the form of incredulous stares. Did my presence mock their aspiration to get the hell out of there? A few took the opportunity to practice the English they had learned at school, leading to lively and mutually interested conversations. Our entire group was invited to an Afghan wedding, a warm celebration that extended well into the night. The couple and their families and friends were among the three million Afghan refugees living in and around Peshawar.

An expedition to the Afghan border above Jalalabad took us to a town populated, so far as was visible on the street, entirely by Kalashnikov-carrying teen-age boys. Women were not to be seen anywhere except a very few in the dark interiors of shops. Even in the 40 (C)-degree heat, they wore head-to-toe black robes, which must have been stiflingly hot. In several shops open for business, you could buy a Kalashnikov for about $14.

The mountain roads zigzagged across numerous stream beds toward Hunza. The roads and bridges had all been built by the Chinese. These transportation routes would be of use to both the Chinese and Pakistani armies in case of military conflict with India. The Chinese, as is their custom, had placed lion-sculptures for good luck at both ends of the bridges. Local people had systematically lopped off all the lion-faces, as graphic depiction of animals or humans was incompatible with their beliefs. With such fervent beliefs, why didn’t they build their own bridges? They could have chosen motifs from their own rich graphic tradition more to their liking.

Hunza was a lovely mountain outpost with terraced rice-fields, views of mountains in every direction, and rough-hewn architecture of a style with echoes of Tibet and Mongolia. The surrounding area was a hotbed of 19th-century ‘Great Game’ intrigue as local tribes played the British, Russians, and Chinese off against each other to maintain their own jealously guarded control. Feats of incredible fortitude were played out in these unexplored and practically impenetrable mountains. I was determined to come back and explore further.

Our entry into China was guarded by young soldiers recruited from far-off coastal regions to enhance the Han-Chinese presence in Xinjiang, with its 20 million Uighurs. Noting the variety of nationalities in our group, the passport-control officer asked suspiciously ‘Why are you traveling together?’ This was so totally outside his limited experience that the question seemed perfectly natural to him. None of us knew what to say, so we asked him to stamp the passports and get on with it.

The road to Kashgar was lined with graceful poplars, as all cities of any consequence in central Asia are. Kashgar was then a wild-West town with a chaotic market in all kinds of livestock including women. Kidnapping of girls to sell as brides was not uncommon. The price might be as high as 20 camels or more, and camels were more valuable than Chevrolets in the trackless wastes of the neighboring Taklamakan Desert. ‘Taklamakan’ means ‘You go in, you don’t come out’. Kashgar had a thriving Uiguhr community, largely self-governing and not subservient to the Chinese authorities. The Uiguhrs lived in cave-like structures honeycombed throughout one large district of Kashgar. Since then, I have read that the Chinese government bulldozed these out of existence to make way for ‘urban renewal’ that no one wanted. Kashgar then was a polyglot mix of Uiguhr, central-Asian, and Chinese nationalities, ethnicities, and eccentricities, all of whom appeared to be co-existing peacefully. Each had its own particular foods, colorful textiles, and other products, in which a lively trade occurred in the central market.

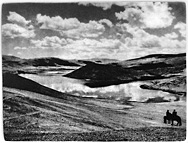

The crossing into Kyrgyzstan was like flipping a switch from Orient to Occident. Suddenly the houses looked European, picket fences sprang up around yards, Western foods appeared in the markets. Peter the Great had seen to it long ago that the furthest outposts of the Russian Empire had a European feeling to them. Forested mountains and abundantly flowing streams made it clear why Kyrgyzstan is called the Switzerland of central Asia. At one stopping-point, a Kyrgyz tribesman allowed me to wear his tribal hat and ride his horse. I was hooked — I wanted to join the tribe, or at least come back for a longer experience of the country than possible with this brief journey.

Almaty, then the graceful capital of Kazakhstan, lived up to its old name of Alma-Ata, ‘Old Apple’, with its broad tree-lined avenues and abundant markets. Wandering into a Russian-Orthodox cathedral, the purest, clearest a-capella singing I have ever heard kept us entranced for an hour or more. As Almaty was the last stop on this trip, a visit to the market scored a kilo of fresh caviar, which, wrapped in old newspaper, made a much-appreciated present to friends in Geneva only a few hours away by air.

Back home in Japan, I mapped out several excursions to the Central and South Asian areas I wanted to see more of. A vast territory, it would need several trips, some by car, others with more foot- or camel-trekking. It took me a couple of years to get various obligations out of the way before I could schedule the proper amount of time. The arrival of the new millennium proved epochal in unexpected ways. The much-publicized Y2K problem turned out to be a non-event, but the pervasive anxiety around it foreshadowed in a skewed way a more ominous turn of events. Like the panic induced by the 1938 ‘War of the Worlds’ broadcast, portents of widespread system failures caused by a computer glitch reflected seemingly unrelated real-world conflict.

In March 2001, people motivated by religious sentiments, similar to those that caused the lion-faces on Chinese-built bridges to be lopped off, blew up the monumental Buddhas at Bamiyan. This required considerable ingenuity in setting up the explosive charges to reduce the entire monument magnificently carved into the mountain to rubble. The bombing was universally condemned, but the general consensus was that no action need be taken because the bombers had ‘only’ attacked a sculpture without killing people. Perhaps they would stop there.

Later that year, as the summertime of long days and lazy heat was slowly winding down, my thoughts again turned to how to go about the Central Asian quest. I decided to eliminate the things I disliked — long hours cooped-up in vehicles without a stop, long-winded guides discoursing on history I would soon forget, shopping, and not enough free time to walk around and spontaneously enjoy the surroundings. September is always a time of renewal, of new plans, of quickening activity as the yearend is in sight; a harvest-time, a time for giving thanks for the bounty of nature, a time for reckoning-up gains and losses, making budgets which carry with them our forecasts, really our hopes and dreams, for the year to come. Shaking off the summer torpor, the pulse quickens, the vigor of autumn animated by the end of the sense of endlessness, the feeling that now is the time to start whatever we hope to do — before it’s too late.

The television was absent-mindedly on one morning, even though nobody was watching it. I saw in passing what looked like a movie, a burning building, people running in panic, firemen running toward the smoke. Smoke and dust obscured the ground-level view, which seemed strange — the movie director should have waited until the smoke cleared. The handheld cameras were unsteady, they kept shifting from the narrow streets to a vaguely familiar-looking bridge, to the view from across a wide river, to an aerial view from a traffic-monitoring helicopter. The TV picture shifted to the Pentagon, part of which seemed to have caved-in. What did that contribute to the story? The sequence was chaotic, it made no sense. Finally an announcer made it horrifyingly clear this was no movie. A passenger airliner had flown into the World Trade Center in New York. How could that happen on a clear day?

Suddenly the flaming building collapsed in on itself. In seconds, office workers, secretaries standing at Xerox machines, executives in their corner offices, messengers delivering urgent messages, were incinerated in the skies above New York and reduced to smoke-filled rubble. The building instantly became the tomb of thousands. Before I could take in the enormity of this mass death, another airplane flew directly into the other tower. This was no accident. That building too collapsed in on itself soon after. As the broadcasters began to piece together the gruesome details — the attack on the Pentagon, the planned attack on the White House foiled by courageous passengers who downed the plane in southwestern Pennsylvania, the demented religious zealots who had carried out the attacks — the president of the United States urged Americans to go shopping. (His advisers feared an economic meltdown, and that was the best they could think of to prevent it.)

World Trade Center

Together with the 3,000-plus lives snuffed out on that day and the destruction of symbolic commercial buildings, the sense of a shared destiny in the world was also shattered. The divisions exploited by warlords and politicians were already there, of course, but this wanton act of mass murder deepened them immeasurably. Since then, self-appointed spokesmen for ‘the world’ or ‘the international community’ have proliferated; their hollow calls for ever-more foreign aid could neither comprehend nor mask the fact that that world of shared destiny had been obliterated.

I realized my Central Asian idyll was over before it could start. For a long while to come, that spontaneous camaraderie that is the essence of international travel would give way to mutual suspicion and fear. Large swaths of the world would become war zones or no-go zones. Visitors would be advised to practice ‘situational awareness’, a heightened threat sense always on the lookout for possible attackers.

Afghanistan, the home of Ghandaran art that mingled Roman, Indian, and Central Asian motifs, would become even more of a war zone than it had been in the aftermath of the Soviet invasion, when I caught only a dusty glimpse of it from the border town outside Peshawar. The verdant Swat Valley of Pakistan had already been taken over by one of the competing death cults spawned by a twisted religious faith, the same one that had harbored the absentee leader of the attacks on New York and Washington. And the newly independent Central Asian nations became staging areas for strategically flawed wars on their borders.

My travels were never burdened by the illusion that my passage would ‘make a difference’ in the lives of the people I encountered. That desperate desire to intervene unasked in other people’s lives is the last vestige of Imperial do-goodism, against which the aid object’s desire NOT to be improved is impervious. Giovanni di Lampedusa’s observations about the Sicilians apply equally to other unwilling aid recipients:

‘The Cardinal of Palermo was a truly holy man; and even now after he has been dead a long time and his charity and his faith are still remembered. While he was alive, though, things were different; he was not a Sicilian, he was not even a southerner or a Roman; and many years before he had tried to leaven with nordic activity the inert and heavy dough the island’s spiritual life in general and the clergy’s in particular. Flanked by two or three secretaries from his own parts he had deluded himself, those first years, that he could remove abuses and clear the soil of its more flagrant stumbling-blocks. But soon he had to realise that he was, as it were, firing into cotton-wool; the little hole made at the moment was covered after a few seconds by thousands of tiny fibres and all remained as before, the only additions being cost of power, ridicule at useless effort and deterioration of material. Like everyone who in those days wanted to change anything in the Sicilian character he soon acquired the reputation of being a fool (which in the circumstances was exact) and had to content himself with doing good works, which only diminished his popularity still further if they involved those benefited in making the slightest effort themselves, such as, for instance, visiting the archepiscopal palace.’

Some people may incidentally benefit from the ministrations of well-intentioned official and unofficial bureaucracies. Infectious disease may be temporarily reduced, projects aimed at food and water self-sufficiency may help as long as the ability to maintain them persists, schools may be built and perhaps even maintained without outside help — all this is commendable, but the place of such activities in the moral sweepstakes is not necessarily superior to all other efforts. The aid organizations’ self-congratulatory reports first of all perpetuate themselves and their lavish fund-raising parties and gabfests, their stratospheric executive salaries, and their rampant corruption, while transferring wealth from the poor of rich countries to the rich of poor countries. Their record of actual effectiveness is often considerably less than advertised.

The artifacts and monuments of ancient civilizations bear powerful witness to their endurance. When savage zealots destroy them, the goal of their rage is to eradicate all memory, to start over. The same desire, to impose mass amnesia, produces mass murder and genocide. There is therefore some survival value to humanity in remembering its past glory in all its various cultural manifestations. When these artifacts are converted into icons of wealth, though, then their civilizing influence is lost. Such is the modern antiquities trade, which has become a criminal enterprise rivaling in its size the drugs and weapons trade. More valuable than the objects themselves is the viewer’s response to them, that sense of being transported through deep time and across vast distances into the world that created them, and to experience that world anew. Whether ancient or contemporary, whatever evokes such a response has inestimable transformative value.

Therein lies the best hope of rebuilding the shared destiny that has since 2001 been subjected to repeated attacks. We cannot restore the pre-2001 world. By recognizing these attacks for what they are, as attempts to destroy memory, to induce amnesia, to substitute fear for love, we can, through person-to-person interaction, create a new sense of what connects all of humanity. Like art, that new sensibility is a creative act. We are still in the midst of imagining it.