Explorer of Cambodia, freedom fighter (Spanish Civil War), Resistance leader, and Gestapo prisoner André Malraux emerged from World War II to write a book that prefigured the World Wide Web. Musée Imaginaire, translated as Museum Without Walls, written in 1947, still resonates today. Great art, he wrote, made accessible to all through reproductions in books, is liberated from the time, place, and history in which they are usually confined by museum categories. Removed from historical context, they can be rearranged in the mind according to aesthetic or philosophical qualities. Malraux drew on the thoughts of Henri Focillon, in La Vie des Formes / The Life of Forms in Art, in suggesting a kind of universal consciousness that all great art responds to. In this way it has the power to transcend the bitter partisan divisions that Malraux knew so well.

Malraux recognized that while taking the great works of art outside of museums liberated them from history, it also threatened to homogenize them into reproducible formats. Everything from the gigantic Sphinx to medieval miniatures assumes the same dimensions in art books, obliterating the effects of scale. Despite the great advances in color reproduction made by publishers like Skira (now Skira-Rizzoli), Alinari, and others, the reproductions were inevitably flat and standardized. They could never really substitute for the originals, nor were they meant to. If they served merely as a reminder of the originals, the creative connection would not be lost. The newest form of this cultural commons is the World Wide Web.

With the Google Art Project, the firm turns its mapping skills to the graphic arts, enabling viewers to zoom-in on artwork in the same way Google-Earth lets them zoom-in on the ground. The familiar slider and plus/minus controls reveal a level of detail in paintings far beyond what can be seen in a museum visit.

These controls thoughtfully disappear after a few seconds of inactivity, easily reactivated whenever the cursor is moved. Bellini’s Saint Francis in the Frick Collection, New York, becomes instantly accessible with all its symbolism —

that flock of sheep, or the stork, or myriad other details that might otherwise have gone unnoticed. The Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Uffizi in Florence, .. At each museum you can wander around the museum virtually as if you were there, in a simulated walk-through the galleries. To examine a particular artwork more closely, click a particular room in the museum’s floor plan, see a list of the artwork in that room at right, and select any for a detailed look in the ‘View Artwork’ mode. Unobtrusive links at right go to brief notes, history, tags, artist information, more works by this artist, and more works in this museum. The ‘Artist information’ links to a Google map showing the artist’s birthplace. Like the artwork, all the information is viewable in any level of detail that may be desired at the moment — brief notes, expandable to more detailed notes, which in turn link to scholarly treatises. The Viewing Notes are straightforward, well-informed, and thankfully jargon-free. Insights gained there can be instantly explored in closeup views.

This musée imaginaire opens up virtually unlimited democratic vistas of exploration for everyone to ‘see for themselves’. If a viewer interprets a detail in a painting differently from that of the conventional wisdom, or wishes to gather evidence for attributing it to a different artist, or sees something amiss, or uncovers a previously unnoticed marvel of the artist’s composition, the tools to do so are immediately at hand. No special permission needed, no off-days, no waiting in long lines or peering over others’ shoulders.

Just as with art books, homogenization-by-format is a risk. Pixels on a screen are not the same as paint on canvas or ink embedded in etching paper. (My Inklings essay looks into this through the innovations in optics, etching, and light-sensitive materials that led to photogravure in the 19th century.)

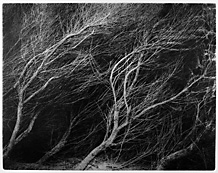

The infinitely varied and unique visual nuances of the originals are reduced to the standard colors of a backlit monitor. Texture disappears. Depth is flattened. Subtleties of tone are dithered into the nearest adjoining pixel-values. All of this obscures the creative forces that bring great art into existence, the formal qualities of tone, color, line, texture, depth, and composition that bypass rational analysis and connect directly with our emotions.

The distinguished contemporary landscape artist April Gornik writes movingly, in her essay An Artist’s Perspective on Visual Literacy on the effects of losing touch with the physical and creative basis of artwork:

We are bombarded to the point of being inured with images, and clearly a vast number of people are increasingly unable to perceive the importance of the physicality of images, even when they are declared to be art. People who are looking at and theoretically being seduced by ads are typically receiving them in a flat manner, the manner of video, the computer screen, billboards, magazines, etc. Their medium is chosen to translate into a wide variety of these information-conveyors. The lowest common denominator of this flatness tends to be photography, and its ubiquitous use is helping erode the perception of physicality in both ads and art. In the case of an advertisement, its materiality is subservient to the message it’s meant to convey, and doesn’t reside in its substance (‘Image is Everything’, as the Canon Camera Company unapologetically reminded us in a popular ad campaign). Its strength is its expediency.

I am a painter, drawer and printmaker of unpeopled landscapes. I came to think about what I perceive as this problem of visual literacy while noticing that, during studio visits to see my work, collectors would often look at large charcoal drawings (which to me look like nothing else in the world) and innocently ask, ‘Is this a photograph?’

The innocent question answers itself soon enough, with a moment’s closer inspection. It is merely the ubiquity of mass-media imagery that narrows viewers’ vision into a standard format they are familiar with. From her own experience, April Gornik observes that looking at artwork with a sense of how it is made enhances our ability to relate it to our own lives. In Vermeer’s View of Delft, for example:

the clouds at the top and the gently curving shore open to the middle of the painting, like an eye opening, into the exterior world the painting reveals. Light in the distance draws us towards infinity and a sense of the immensity of space extending limitlessly out from us, but which Vermeer presents with great intimacy.

[I]n the same way that a painting holds within itself the history, time, and the tale of its formation, a person looking at it is informed, enriched, and is subliminally able to experience all of that input. This physicality, the way an art object is ‘built’, speaks to us, and our response is an affirmation of our own sensory abilities, forming a connection and an interface of time and space, intent and emotion, even history.

A painting in the flesh is, and should be, a somatic experience for the viewer. An image painted by hand, rather than reproduced in a magazine, contains in its painted surface a person, a world, in the manner in which the paint is applied and the object made, be it realistic or abstract.

The real power of visual art is its capacity as virtual reality to create a complex physical experience. Painting is so specifically powerful, and more powerful than other mediums, because an artist who makes one builds into it their actual experience, including decision-making, intent, corrections, and (importantly) actual time passed. Paintings generate all this experience back to the viewer. The summary that a painting is of all that activity is capable of both holding and regenerating that experience. The object powers the somatic connection that remains between the work of art, the artist who made it, and the person looking at it. That connection is an essential part of the human experience, a verification of humanity, history, and our connectedness itself.

I would only add that original printmaking equally embodies the personal experience of the artist, and takes equal part in the connectedness of human experience. April Gornik’s paintings certainly testify to the truth of her observations. The Google Art Project, like Skira’s art book, is only a technology — a fascinating, wonderful bounty that will enable discovery and enjoyment for many years to come, with a creative energy of its own, expanding the territory of the cultural commons. It is a marvelous resource for artists and collectors alike to stay in touch with their senses and with the creative forces of art and the human experience.

Henri Focillon’s La Vie des Formes is available in French at no cost from Project Gutenberg. and from the University of Quebec at Chicoutimi (dans le cadre de la collection: ‘Les classiques des sciences sociales’ dirigée et fondée par Jean-Marie Tremblay, professeur de sociologie au Cégep de Chicoutimi).