Interview with Peter Miller by Rfoto folio

Translation of Peace in the Work of Peter Miller

RF: Would you please tell us a little about yourself?

PM: I'm from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S.A., a northern outpost of Appalachia with three rivers, many hills, onion-domed churches, lots of snow in the winter, a former iron and steel center. I graduated Columbia in New York, did a Ph D in sociology at Berkeley, and consulted for clients at Stanford Research Institute. One of these was Honda, who brought me to Japan in 1977 to help with their first U.S. auto plant. After some back-and-forth, I stayed, and have lived in Japan since 1981. I continued consulting for various high-tech clients, and again as chance would have it, one of these made an ultraviolet light source for the printing and semiconductor industries. Coincidentally I had seen the 19th-century photogravures of Peter Henry Emerson at a 1989 museum exhibit, and learned that this technique uses ultraviolet light. I moved from Tokyo to Kamakura in 1991, built a photogravure workshop, taught myself the photogravure technique, and held the first exhibit in an unused store in Kamakura the following year. In the 25 years since I started doing photogravure, I've held some 40 exhibits in Japan, America, France, England, Germany, Italy, Lithuania, and Russia, among others. These days, I'm organizing exhibits with other artists in an effort to see what contemporary Asian art means to viewers around the world.

RF: How did you get started in photography?

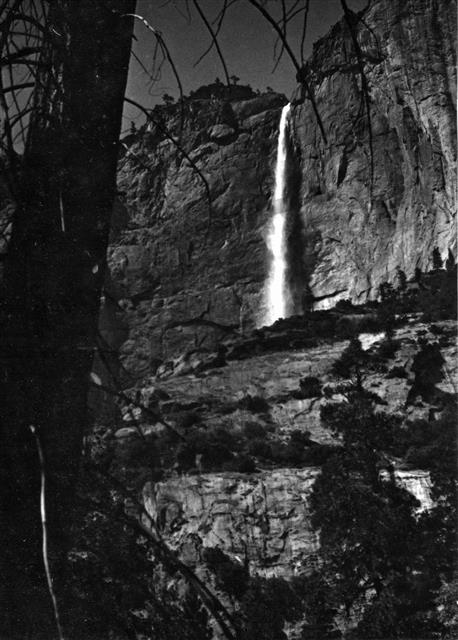

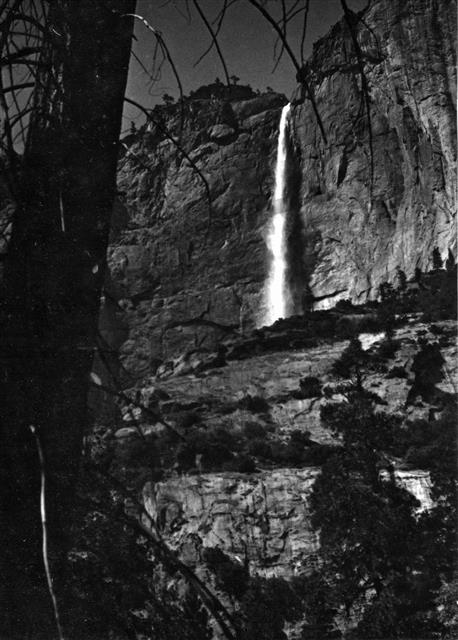

PM: From the age of six, photography was my way of exploring my surroundings in Pittsburgh. Through a primitive box camera I looked at snow scenes, railroad tracks, steel mills, light-and-shadow patterns, people in various ethnic neighborhoods, streetcars, amusement parks, friends -- whatever caught my eye. Later I set up a home darkroom; that was then the fastest way I could get to see the images. I recall winding rolls of 35-mm film onto stainless-steel reels and immersing them into tanks of home-made developer and fixer. Traveling West, I worshiped nature, mesmerized by the grand visions of Ansel Adams and others. In college, I did some covers for Columbia Review. Moving to Japan unleashed other interests as I explored this new (to me) environment photographically. I resumed an interest in mountain-climbing and skiing, becoming the first foreign member of the All-Japan Alpine Photographers Association.

PM: From the age of six, photography was my way of exploring my surroundings in Pittsburgh. Through a primitive box camera I looked at snow scenes, railroad tracks, steel mills, light-and-shadow patterns, people in various ethnic neighborhoods, streetcars, amusement parks, friends -- whatever caught my eye. Later I set up a home darkroom; that was then the fastest way I could get to see the images. I recall winding rolls of 35-mm film onto stainless-steel reels and immersing them into tanks of home-made developer and fixer. Traveling West, I worshiped nature, mesmerized by the grand visions of Ansel Adams and others. In college, I did some covers for Columbia Review. Moving to Japan unleashed other interests as I explored this new (to me) environment photographically. I resumed an interest in mountain-climbing and skiing, becoming the first foreign member of the All-Japan Alpine Photographers Association.

I have always responded to new experiences visually and photographically. Putting together a coherent series of images, it seems, is a way of making sense of the unknown. In doing so, I avoid 'must-see' sights and just walk around or take trams to discover what is visually interesting, as I did as a child in Pittsburgh.

RF: Which photographers and other artists work do you admire?

PM: Peter Henry Emerson, an American who practiced photogravure in England in the 1880s and 1890s, inspired my own efforts. The marvelous simplicity and tonal subtlety of his images of the Norfolk tidelands and its people continue to inspire. In the etchings of Rembrandt, every line matters, the extraordinary range of tone is matched by an equally extraordinary range of emotion. The Japanese ink-brush painters Sesshu and Sesson developed a similarly wide range of tonal and emotional expression in a very different context. Whistler's etchings evoke the shimmering charm of Venice even in its backwaters -- he was really the first Impressionist, before the name existed. In the 20th century, Stieglitz and Coburn, both of whom did photogravure, exalted the mystery of urban imagery. Jackson Pollock brought American art to a pinnacle in mid-20th century Abstract Expressionism with an energy and verve that have never since been surpassed. Among recent photographers, Wynn Bullock stands out as one who explores in depth the mystery of life.

RF: Would you share with us an image (not your own) that has stayed with you over time.

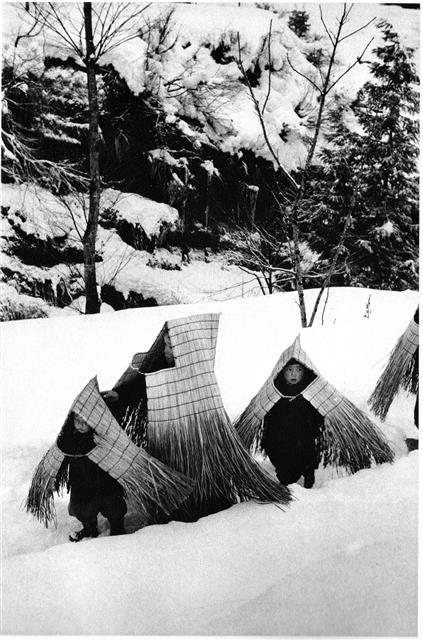

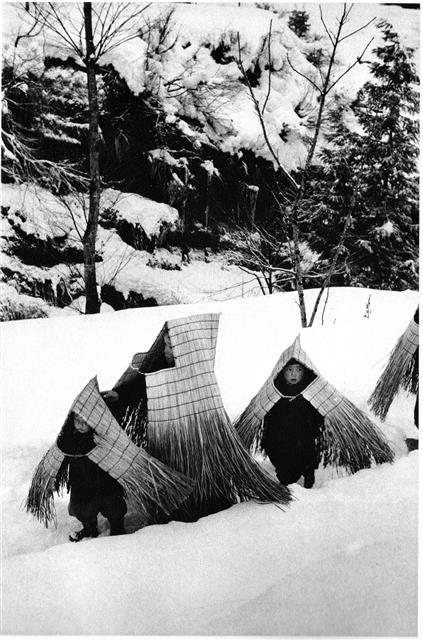

This photo by Hiroshi Hamaya of a village called Tokamachi, in Japan's snow country, evokes the furusato (hometown) feeling through children on their way to school fitted-out with rice-straw that looks like wings, making them symbols of the life that will emerge in the spring. Simple and profound at the same time, Hamaya's photo transforms an ordinary moment into a vivid recollection, which is why it stays with me.

RF: If no one saw your work, would you still create it?

PM: With any artwork, it's good to ask 'Who is this for?' For people who have had enough of the excessive perfection of computerized graphics, there is a strong desire for hand-made images and objects. I think of the micro-landscape of the etched copperplate as akin to wabi-sabi -- rough, imperfect, asymmetrical, unfinished. If in printing the plate I can impart that quality to the prints, that sense of craft and Japanese sensibility is what the people who acquire my prints are looking for. Yet if the prints are made only to satisfy clients, something is lost, the style becomes mannered and boring. To stay fresh, it has to have that spark of spontaneous chance that sets it apart from the glossy perfection of goal-oriented behavior. I have to ignore pre-existing demand at first, then consider it anew after the prints are made.

RF: Why photogravure etchings ?

PM: There's nothing like the depth, texture, and tonality of intaglio for connecting sight and touch, for going directly to 'the heart of the matter'. More than a century-and-a-half after photogravure was invented -- by Talbot in England and Niepce in France -- the way it enlivens the world we think we know is still magical. The archival quality of photogravure is ensured by carbon-based inks, which last for eons, which is why carbon is used for geological dating. Photogravure is part of the same lineage as engraving, etching, and aquatint going back to the 1500s with Durer, Rembrandt, and Goya.

RF: Please tell us about your process and what the perfect day of photography is for you.

The photo is the beginning. No, imagination is the beginning. No again, it's really a matter of being open to the unexpected, guuzen-sa as we say in Japanese. Now you can't search for surprises, and that's the point: to free yourself from any purpose. I don't try to record, document, or capture anything. If I'm looking for anything at all, it's an arrangement of light-and-shadow that corresponds to some state of mind. I look for qualities that lend themselves to the particular ink-on-paper (or washi) look of photogravure, like depth, texture, and tonality, that are independent of any subject matter. Different kinds of light-and-shadow balance, near-to-far progression, distribution of sharp focus versus haze, might be found in natural forms such as fog, rock surfaces, skin, sand, waves, trees, etc. These might give rise to emotions such as the sense of foreboding associated with dark clouds, or the sense of mystery associated with reflections, or the joy of something luminous. How marks on paper trigger memories and emotions is a curious feature of thought. When those correspondences between a state of mind and what's visible 'out there' spring up, that's a good day.

Photogravure etching needs an abundance of time, slow time. Since 1991, I've created, etched, printed, and published 328 editions. That's about one per month. Selecting from among numerous photos those that are worth this amount of time and effort involves asking for each image, why do this. I exclude anything that cries out for some stock response, any hint of snark or lack of respect for the subject, and anything that might appear staged. Finally, I look for specifically Japanese qualities, regardless of whether the scene originates in Japan or not.

RF: What challenges do you face as a photographer?

PM: Finding a perspective that encompasses the whole experience, because often the various elements are far apart. Video is very good at putting together related images in emotional sequence. In still photography, the challenge is to see all of these 'at a glance'. Another challenge is removing the clutter. Many photographers don't bother, justifying their approach on the grounds that they take the world as they find it, as in the genre known as street photography. But the world as it is is awfully cluttered, and really much of the clutter is better forgotten, like many of the snapshots in that genre. It may be true that hidden gems await discovery in garbage, but you have to look through a lot of garbage to find them. I would rather search for scenes of glory in plain view.

RF: If you could go out and shoot with another photographer living or passed who would it be ?

PM: Tetsuya Noda, because he is so good at noticing things -- stray details that on second glance turn out to be significant. I would like to witness the thought process that transforms personal observations of apparently fleeting interest into images that live on independently of their sources. Many try to do this; few succeed.

RF: How do you view this time in the history of photography?

PM: Advances in computer technology in every phase of image-making, from recording to storage, processing, printing, publishing, communicating, and other forms of sharing, have opened up previously undreamed-of possibilities in photography. We have hardly even begun to explore the creative potential of image-processing software. The technology advances, but our minds have a hard time keeping up -- for example, it's still generally accepted that photographs render a true picture of events, people, objects, documents, etc.

In video and film, we appreciate extensive editing, even in documentaries, yet still photos that are edited or staged lack authenticity. Until a consensus of acceptable still-photo editing emerges, photography will continue to be held back from realizing the great potential of the available technology. Before photography, Canaletto, Vermeer, and others used lenses to outline their paintings -- but they didn't just copy what they saw through the lens, they re-arranged buildings, people, interiors to suit their own aesthetic purposes.

Advances in computer and communications technology enable real-time war broadcasting, turning viewers into spectators of carnage beyond Hollywood's bloodiest dreams. At the same time, public access to all the world's museum art collections is growing exponentially, vastly enriching imaginary potential. Instant sharing of snapshots has generated a tsunami of trivia, adding to those of the mainstream media, of which some infinitesimal fraction may hold enduring interest. This visual environment challenges every artist to create images that somehow distinguish themselves, endure in memory, and become part of the cultural commons. So, when people tell me they remember a photogravure etching of mine from an exhibit five years ago, I am reminded anew of what an extraordinary feat it is for that image to have persisted through the millions of others that have flashed before their eyes.

This results in part from the unique qualities of photogravure etching in contrast with nearly everything else we see, and (I like to think) my own vision and practice of the technique. Advances in computerized imagery have generated a corresponding desire for hand-made graphics, like photogravure etching. The present is a time of greatly expanded creativity for photography and all the graphic arts.

RF: How do you overcome a creative block?

PM: By doing something unexpected, seeking out new experiences, experimenting with a previously untried variation on the photogravure technique, allowing myself to respond without restriction to a new situation, place, or person. For example, I am looking into sun-exposure of the ultraviolet resist.

Re-reading old manuals of technique, re-viewing artwork that once inspired me, reading my etching and printing notes, searching for something on the Web and letting the search go in serendipitous directions -- all these things stimulate new approaches.

Travel almost always stimulates creative endeavor, if there's enough time after dealing with all the logistics and gatekeepers to reflect on what one is experiencing.

RF: What do you hope the viewer takes from your images ?

PM: More ability to observe their surroundings, to notice interesting things great and small that might otherwise escape their attention: Above all, to see for themselves, develop their own preferences, and let the art in their own surroundings take them on journeys of discovery.

RF: Would you like to share a story about one of your images?

PM: The print Broth of Life, is a scene of the kombu (kelp) harvest in Erimo, Hokkaido, source of the daily soup. Just as we arrived at Erimo, a four-year-old girl spontaneously took my hand and led me to where her family was spreading out the kombu to dry on the rocks. She introduced her friends, then her pet seal, which turned out to be a piece of driftwood that looked very much like a seal. From that vantage-point, the view of the entire length of drying kombu appeared -- thanks to Naoko-chan.

RF: How does your art affect the way you see the world?

PM: The forms, textures, and shapes of ink on paper or washi are more real to me than the so-called real world. Without neglecting practical necessities like paying for supplies or getting from place to place, I try to devote as much time and energy as possible to this internal universe, which is the essence of freedom. Distractions with their absurd claims of priority deprive us of this freedom. They try to reduce art to just another commodity like a brillo pad or a soup can, or worse, to an argument about a topical issue. That's why the promoters of conceptual art insist on removing every shred of personal subjectivity and craft from their products, as if by so doing they could make it objectively true, beyond challenge. That ambition is of course nonsense. The artist's responsibility is to use one's own subjective response to draw out meanings and possibilities from the stuff of everyday life.

Photogravure etching does not forgive errors of technique. I cannot blame anyone else, or society, for my mistakes. The good news, though, is that I can find out what went wrong. Through a series of error-corrections (of everything from ultraviolet exposure to platemaking to printing), improvement and success are possible. In the workshop as in other endeavors, distinguishing actual from wished-for results, and acknowledging and learning from one's own faults, is the way to succeed.

While we cannot escape irrational forces in international or personal relations, we can offset them with what might be termed irrational counter-forces. Art is one of these, along with music, religion, science, and other creative endeavors. All of these cultural artifacts stimulate irrational counter-forces in a positive way. These activities are vitally important for the overall welfare and health of society because they are the only effective resources we have for opposing and neutralizing the demoniacal forces unleashed by tribal ideology and war.

RF: Where can we see your work?

PM: The prints can be seen at:

https://kamprint.com/ and https://kamprint.com/xpress/

Also:

https://kamprint.com/views/ (blog) and

https://www.facebook.com/photogravure (quick updates)

The original prints can be ordered through either the kamprint.com site or the kamprint.com/xpress (Japanese) site, by clicking the link on any full-screen page, or by sending me an email to z3ix [at] kamprint.com. New prints are posted to my website and to Facebook after I have started printing the editions, and 'Liking' The Kamakura Print Collection page there is a good way to stay informed. Selected prints are also available from the dealers listed below or at my websites.

Photogravure etchings are made from an aquatinted copperplate etched to various depths through a permeable resist, the resist having previously been exposed through a transparency with ultraviolet light, then adhered to the copperplate. Prints purchased on-line are free of postage and all other charges, besides the cost of the print itself. To order an original photogravure etching, please click the  icon at the lower-right of any full-screen page, (like this one). Please allow about a week after ordering for delivery. For further information, please ask by email , or arrange a convenient time for a Skype (name: 'kamprint1') or landline call.

icon at the lower-right of any full-screen page, (like this one). Please allow about a week after ordering for delivery. For further information, please ask by email , or arrange a convenient time for a Skype (name: 'kamprint1') or landline call.

Viewers may also complete the Japanese inquiry form or the Japanese order form in any language. Payment for prints delivered in Japan may be made by C.O.D. (着払).

Site: Home・ホーム; Viewing・見聞; Learning・情報; Purchasing・ご注文; News ・ ニユース; Videos・ビデオ Xpress

Series: Temples・寺; Dreamscapes・夢; Seascapes・海; Furusato・ふるさと; Pathways・道; Mongolia・モンゴル; Acts & Scenes・町; Unseen・見残す; New Prints・新

Inklings essay Collecting prints Framing tips Technique Investing Health Links

Original photogravure etchings seen at this site are available by clicking the order button on any full-screen image page, or from these fine print dealers:

Baltimore: Conrad R Graeber Fine Art, Box 264, Riderwood, Md, U.S.A., tel +1-410-377-6713

San Francisco: Japonesque, 824 Montgomery Street, SF, Ca, U.S.A., tel +1-415 391-8860

Vladivostok: Arka Gallery, 5 Svetlanskaya St, Vladivostok, Russia, tel +7-4232-410-526

PM: From the age of six, photography was my way of exploring my surroundings in Pittsburgh. Through a primitive box camera I looked at snow scenes, railroad tracks, steel mills, light-and-shadow patterns, people in various ethnic neighborhoods, streetcars, amusement parks, friends -- whatever caught my eye. Later I set up a home darkroom; that was then the fastest way I could get to see the images. I recall winding rolls of 35-mm film onto stainless-steel reels and immersing them into tanks of home-made developer and fixer. Traveling West, I worshiped nature, mesmerized by the grand visions of Ansel Adams and others. In college, I did some covers for Columbia Review. Moving to Japan unleashed other interests as I explored this new (to me) environment photographically. I resumed an interest in mountain-climbing and skiing, becoming the first foreign member of the All-Japan Alpine Photographers Association.

PM: From the age of six, photography was my way of exploring my surroundings in Pittsburgh. Through a primitive box camera I looked at snow scenes, railroad tracks, steel mills, light-and-shadow patterns, people in various ethnic neighborhoods, streetcars, amusement parks, friends -- whatever caught my eye. Later I set up a home darkroom; that was then the fastest way I could get to see the images. I recall winding rolls of 35-mm film onto stainless-steel reels and immersing them into tanks of home-made developer and fixer. Traveling West, I worshiped nature, mesmerized by the grand visions of Ansel Adams and others. In college, I did some covers for Columbia Review. Moving to Japan unleashed other interests as I explored this new (to me) environment photographically. I resumed an interest in mountain-climbing and skiing, becoming the first foreign member of the All-Japan Alpine Photographers Association.

icon at the lower-right of any full-screen page, (like

icon at the lower-right of any full-screen page, (like  into your email (日本語 OK).

into your email (日本語 OK).