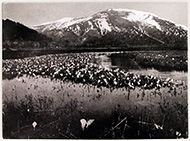

For Saint Francis and his followers, the landscapes of Tuscany and Umbria recalled the Holy Land. At Assisi, the arid clear air that collapses distance was as congenial to visionary thought as in the desert and mountains of Sinai. But Saint Francis returned most often to La Verna, a mountain north of Arezzo, where fantastic, apparently gravity-defying rocks and mists in the trees atop Monte Penna, lent an other-worldly atmosphere. Saint Francis’ sympathy with all living beings and his gospel of the simple life, though articulated early in his ministry, received further sustenance here. In 1213, Count Orlando Cattani, impressed with Saint Francis’ philosophy, donated the mountain to him and his followers, describing it as suitable for contemplation and prayer.

Here the Franciscans lived a simple life in harmony with nature. Here too, near the end of his days, in 1224 Saint Francis is believed to have received the stigmata of Christ which in the eyes of the faithful confirmed his sainthood. The Bellini painting (in the Frick Collection, New York) conveys the spiritual splendor of this event. Saint Francis stands barefoot, as on holy ground, with hands outstretched amid a landscape full of symbolism. The quivering tree at upper left, mysteriously illuminated, recalls the burning bush of Moses, whom the Franciscans regarded as a spiritual ancestor. Water trickling from a spout in the rocks at lower left also recalls Moses’ miraculously bringing forth water from the rocks at Horeb.

Saint Francis did not ‘renounce the world’, nor did he ever become ordained as a priest. He re-defined happiness as something to be experienced in this world, not to be indefinitely postponed until the next, finding it in the simple life around him in nature, in the spiritual vitality of all creatures — even the birds found his ministry enchanting. He taught suppression of desire as the road to happiness, knowing that, beyond the essentials of life, it is not the lack of things, but the mindless grasping for them, that causes suffering.

Far from Chiusi La Verna but similar in spirit, around the same time, Zen philosophers were discovering in the conscious suppression of desire, reverence for nature and for all creatures, and the cultivation of simplicity a route to happiness. This is not to suggest that Saint Francis was channeling Zen, only that experience and contemplation in vastly different traditions led to remarkably similar ways of life.

The present-day Santuario La Verna has electricity but no TV, and no heat until Oct 15. It was unusually cold in early October, down to 5 C., but in keeping with the spirit of the place, I didn’t complain, and actually got used to it. But then a ‘miracle’ occurred: The authorities decreed an early start to the room-heating season. Guests are few during the week, more on the weekends. At an investiture ceremony for new priests, the church was full, with people standing in the aisles. I was so accustomed to seeing dark deserted churches that this semi-chaotic scene of families gathered, babies crying, old friends meeting, and the combination of solemnity and joy suddenly seemed the way it was meant to be experienced. The paintings, the finely carved confessional chambers, the candles and everything all ‘fell into place’ amid this throng of celebrants.

(Click image for photogravure etching of Chiesa La Verna.)

The Franciscans retain their devotion to the simple life, unsentimental and practical, doing what they can by example rather than by admonition. They don’t provide much guidance as to procedure at the convent, leaving each to find his own way. The bells, which have a clear, long-lasting tone, remind you of meal-times and other events. (Hear the bells of Chiesa La Verna.) Meals in the refectory are plain but adequate, with home-made pasta, vegetables, soup, meat (fish on Fridays), bread, and table wine. Well-marked hiking trails in the area lead to Mount Penna and to nearby villages.

Santuario La Verna

santuariolaverna@gmail.com

Tel: 0575-5341

Piero della Francesca: Painting, Perspective, and Accounting

In nearby Sansepolcro, Monterchi, and Arezzo, the frescoes of Piero della Francesca (1412 – 1492) express religious devotion together with an uncanny presence in this world. His saints are vulnerable human beings, beset by fear and anxiety. They don’t look like cherubs or sages. He depicted a pregnant Madonna, the Madonna del Parto, using blue pigment made from lapus lazuli imported by a Venetian merchant from Afghanistan. The fresco is in Monterchi, where Piero’s own mother was born.

His magisterial Legend of the True Cross brings a complex multi-century story to life through a series of realistic incidents. Throughout this narrative, his figures have a ‘wooden’, almost Byzantine quality, as if exposed in a ‘decisive moment’ in mid-motion. Yet they are also very much alive, with a variety of human expression, engaged in a direct way with the viewer. Their equilibrium and their activity are in perfect balance. Each painting is an instant of time, for all time.

Most remarkable of all is Piero’s painting of Jesus Christ’s Resurrection. Given the challenge of depicting a miracle, Piero does so without resort to pyrotechnics, showing Christ rising from his coffin, as if from sleep, above four slumbering Roman soldiers.

Behind, at left, the trees are barren, while at right, they are flourishing. The painting is thus divided with mathematical precision, itself symbolizing a renaissance in its composition and perspective. Christ’s figure is one of prodigious strength, his expression stunned at this unexpected renewal of life, yet soldiering on, flag in hand. Robed, unusually, in pink, symbolizing the dawn of a new era, he appears determined to carry on right where he left off when interrupted.

In addition to painting, Piero della Francesca also published treatises on geometry, the five platonic solids, perspective, and mathematics, one of which formed the basis for modern accounting! Although another native son of Sansepolcro, Luca Pacioli (1446 – 1517), is generally credited as the ‘father of accounting’, Pacioli actually learned it from Piero della Francesca, who developed the mathematics of double-entry bookkeeping based on the practices of Venetian merchants with which he was familiar. Truly a Renaissance man, from whom Leonardo da Vinci later drew inspiration and guidance, Piero della Francesca clearly exemplifies the art-inspired view of life that is the focus of this blog.

Sources:

Idle Speculations

Rona Goffen, Giovanni Bellini (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989)

John V. Fleming, From Bonaventure to Bellini: an Essay in Franciscan Exegesis (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, c l982)

Luca Pacioli